Autologous Corneal Repair Using in-vitro Adult Stem Cell Expansion

Peter J Wilson, Jeremy J Mathan, Jennifer J McGhee, Salim Ismail, Trevor Sherwin

Affiliation

Department of Ophthalmology, New Zealand National Eye Centre, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand

Corresponding Author

Professor Charles McGhee, Department of Ophthalmology, Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences, The University of Auckland, Level 4, 85 Park Road, Grafton, Auckland Private Bag 92019, Auckland, New Zealand; Tel: +6493737599; E-mail: c.mcghee@auckland.ac.nz

Citation

McGhee, C., et al. Autologous corneal repair using in vitro adult stem cell expansion. (2016) J Stem Cell Regen Bio 2(1): 1-7.

Copy rights

© 2016 McGhee, C. This is an Open access article distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Keywords

Human cornea; Limbal stem cell physiology; Ex-vivo expansion; Transplantation

Abstract

The human cornea requires a smooth, transparent, robust and renewable surface to maintain its key optical and protective functions. The corneal epithelium is maintained by a local population of “stem cells”, which although not truly pluripotent, are capable of self-regeneration by asymmetric division. These cells are located at the limbus - the region where the conjunctiva-covered sclera meets the cornea. The widely accepted “XYZ” hypothesis of corneal epithelial maintenance postulates that limbal stem cells give rise to transient amplifying cells, which migrate and mature in both a centripetal and anterograde fashion towards the corneal surface. Many diseases and injuries to the limbus can cause the loss of this vital reservoir of cells and, due to subsequent surface irregularity and loss of corneal transparency, result in severe visual impairment, including blindness. Indeed, in some regions of the developing world corneal blindness may be more prevalent than cataract blindness. Such corneal blindness was previously irreversible, but over the past 30 years it has been possible to improve or restore vision using limbal “stem cell” transplants. Pioneering techniques required large tissue grafts that could compromise the donor eye, but recent developments allow the harvesting, ex-vivo expansion and transplantation of limbal stem cells from relatively small biopsies. In this review we outline limbal stem cell physiology in health and disease, describe our surgical approach to limbal stem cell deficiency, illustrate results of this intervention in our practice, and consider current and future advances in this arena.

Introduction

Blindness due to corneal disease is second only to cataract in causing visual loss world-wide[1]. A variety of diseases can cause corneal scarring, including chemical or thermal burns, inflammatory or autoimmune pathologies, connective tissue diseases, and infections such as trachoma (Table 1). These conditions can all result in progressive corneal opacification and replacement of the corneal epithelium with conjunctival epithelium. In end-stage disease, the corneal epithelium is unable to regenerate due to loss of the “stem” cells that reside at the junction between cornea and conjunctiva.

Table 1:

| Category of disease | Examples |

|---|---|

| Injury | Chemical injury, especially alkali[2] Thermal injury Surgical, e.g. cryotherapy |

| Inflammation / Autoimmune | Stevens-Johnson syndrome Ocular cicatricial pemphigoid[3] Rosacea keratitis |

| Infection | Trachoma[1] |

| Inherited | Aniridia[4] |

Causes of corneal scarring and limbal stem cell failure

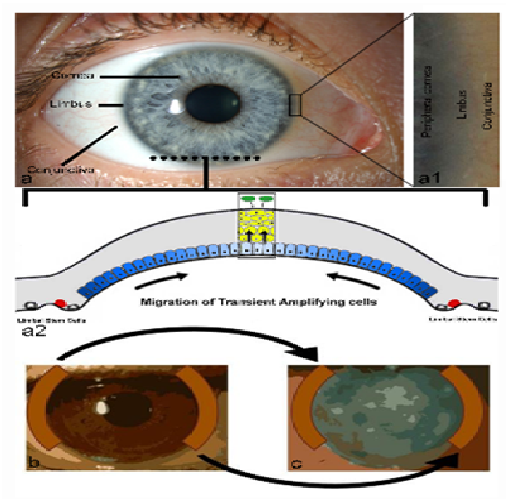

Although the cells that replenish the corneal epithelium are not true multipotent stem cells (they do not differentiate into several cell types in vivo), they are unipotent stem cells capable of extended self-regeneration, and are commonly referred to as limbal stem cells within the ophthalmic literature[5]. To maintain the healthy ocular surface, limbal stem cells resident within the palisades of Vogt, replicate and migrate centripetally as corneal basal epithelial cells, which then mature and migrate to the ocular surface prior to shedding (Figure 1). This cycle of epithelial maintenance has been referred to as the “XYZ” hypothesis: “X” equals proliferation of the basal cells; “Y” represents centripetal migration; and “Z” the shedding of cells from the corneal surface[6]. In active disease the proliferation and migration of epithelial cells may be inhibited, but the epithelium will eventually recover if the limbal stem cells are preserved and the ocular environment optimised.

Figure 1: Anatomy and stem cell biology of the anterior ocular surface and limbal autograft; The anterior ocular surface (a) is composed of the transparent cornea and peripherally located conjunctiva separated by the transitional limbus, magnified in a1, which is the in vivo location of epithelial stem cells. In the cross sectional diagram (a2) stem cells (red cells) at the limbus give rise to transient amplifying (TA) cells (blue cells) by asymmetric division. The TA cells migrate over the corneal surface repopulating the basal epithelium. Further division and differentiation produces mature epithelial cells (yellow cells) and the anterior direction of these cell processes result in a stratified epithelium (box) prior to loss of epithelial cells (green cells) from the corneal surface by desquamation. In limbal autograft procedures, approximately 40-50% of limbal tissue is taken from the healthy limbus (b) and sutured to the diseased limbus (c) – usually combined with a superficial keratectomy to remove all abnormal, superficial, vascularised corneal tissue in the diseased eye.

However, if the limbal stem cells are destroyed, the corneal epithelium cannot be replenished, instead being replaced by the neighbouring conjunctival epithelium. In contrast to corneal epithelium, conjunctival epithelium is irregular, translucent, with an underlying vascular stroma that severely limits the passage of light and quality of vision. Early signs of limbal stem cell deficiency (LSCD) include a swirled/vortex appearance of the corneal epithelium, often in a triangular formation with the apex pointing towards the centre of the cornea. This is thought to represent disorganisation of the epithelium, with loss of tight junctions and encroachment of conjunctival epithelium. As disease progresses, the cornea loses its transparency, and eventually becomes vascularised.

Traditional medical therapy for LSCD has been supportive, including copious lubricating preservative-free eye drops, antibiotics to protect against infection in the context of an epithelial defect, and corticosteroids to reduce associated inflammation. The importance of a healthy ocular environment has also been recognised, with trials including clinical application of growth factors and cytokines[7], the most common being autologous serum eye drops. Physical measures of protection have also been adopted, including amniotic membrane grafts, and closing the eye partially or totally with eyelid surgery (tarsorrhaphy) or a botulinum-toxin-induced ptosis. However, none of these treatments address the underlying pathology, namely the lack of a source of epithelial cells to replenish the ocular surface. Unfortunately, the natural history of LSCD is a progressive deterioration of corneal integrity, with resultant conjunctivalisation and profound loss of vision.

Recognising that corneal epithelium is derived from a reservoir within the limbus, attempts to treat LSCD have focused on restoring a population of viable limbal stem cells. In transplant surgery, there are three potential sources of tissue: from the patient (autograft), from another person (allograft) or from an animal (xenograft). The first series of transplant of limbal tissue to treat LSCD was reported by Kenyon and Tseng[8] and involved an extensive autograft from the patient’s contralateral limbus, including adjacent conjunctiva, cornea and underlying lamellar dissection of sclera (Figure 1). Although this technique yielded promising results in eyes with end-stage disease, it had significant drawbacks, including risks associated with harvesting large volumes of tissue from an otherwise healthy eye; the incorporation of bulky tissue in the host site; and inability to repeat surgery due to insufficient residual tissue in the donor site[9].

In an attempt to minimize surgical trauma to the donor eye, Pellegrini[10] proposed a limited limbal biopsy. This small sample was sufficient for in vitro expansion that could then be transferred to the diseased eye. Various substrates have been proposed for this purpose, including amniotic membrane, contact lenses and fibrin[11-13].

Both of the above transplant techniques are dependent upon a healthy fellow eye from which stem cells may be harvested. If damage is bilateral, then tissue must be obtained from another source, with the attendant risk of allograft rejection[14]. The closer the tissue type is to that of the host, the lower the risk of rejection, and therefore a close family member donor is preferable to allogenic material from living or cadaveric donors.

Limbal stem cell expansion technique

Over the past six years the preferred treatment regimen for unresponsive LSCD within the clinic of the senior author (CNJM) has been in vitro autologous limbal stem cell expansion using amniotic membrane as the support/transplant vehicle. We describe here the methods and outcomes of four selected treatments of twelve performed during the described period. The four cases are described in detail above with a summary provided in (Table 2).

Table 2:

| Case | Side | Sex | Age at injury | Pathology | 1st VA | Date of LCST | Surgical procedures | Follow-up months | Final VA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | L | M | 42 | Caustic soda | P of L | 23/07/09 | Two LSCT, PKP and phaco/IOL | 63 | 20/40 |

| 2 | R | F | 36 | Plant extract | P of L | 31/07/14 | One LSCT, two PKP, phaco/IOL | 10 | 20/50 |

| 3 | L | M | 21 | Firework | CF | 20/08/09 | One LSCT, PKP | 34 | 20/30 |

| 4 | R | F | 11 | Penetrating Eye injury | P of L | 01/10/10 | One LSCT, four PKP's | 2.5 | 20/80 |

Summary of nature of injury, presenting and final acuities of the selected cases. l (left eye); r (right eye); m (male); f (female);P of L (perception of light); CF (counting fingers); LSCT (limbal stem cell transplant); PKP (penetrating keratoplasty); Phaco/IOL (phacoemulsification/intra-ocular lens)

Amniotic membrane was supplied by the New Zealand Eye Bank, having been prepared from donated placentas and stored at -80°C in a 50/50 mixture of glycerol/BSS with Antibacterial- Antimycotic mixture (Anti-Anti, Gibco). The amnion was thawed and treated with TrypLE Express (Gibco) and rinsed with PBS (Gibco). It was wrapped around a scaffold with the basement membrane uppermost and placed in a 5 cm petri dish with lid. It was kept moist with PBS until the addition of the limbus biopsy.

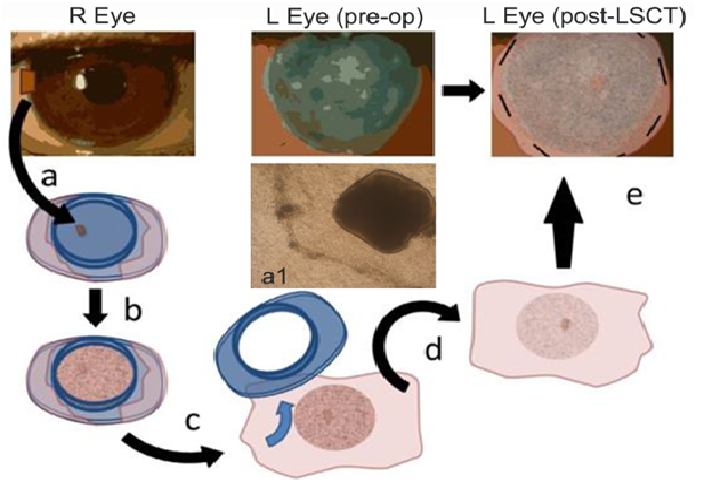

Autograft donor material was obtained from one or two small biopsies of the patient’s limbus performed under local anaesthetic then transported to a cell culture laboratory in a sterile dish containing culture medium (Figure 2). The 1.0 mm to 1.5 mm biopsies were transferred to the basement membrane of the prepared amniotic membrane. After 5 minutes the specimen was overlaid with 400 μl of culture medium. A further 1 ml was added the next day. The explants were cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 21 days. The culture medium consisted of DMEM/F12 (Gibco) with 10% autologous serum, Insulin Transferrin Selenium (ITS, Sigma), GlutaMAX and PSN antibiotic mixture (both Gibco). Culture medium was replaced every 3 days and spent medium analysis showed no contamination during any of our expansion protocols. Over the course of 2 - 3 weeks, the cells expanded to create a confluent layer greater than the area of the cornea.

Figure 2: Limbal stem cell expansion and implantation. One or two 1.0 to 1.5 mm biopsies are taken from the limbus of the healthy contralateral eye and placed on amniotic membrane that has been wrapped around a culture well (a). Phase contrast microscope image of outgrowth from a 1 mm² limbal biopsy on amnion in vitro (a1). The cells proliferate to confluence over the course of 2 - 3 weeks (b). In the operating room the well is removed from the graft (c). The graft is inverted (limbal stem cell expansion facing down) (d) and placed on the diseased cornea where it is sutured in place (e).

The epithelial cell outgrowth from the explanted tissue was observed by inverted microscopy and dark field microscopy (Figure 2). Outgrowth occurred in a radial manner and confluent growth was achieved from all explants prior to the planned day of surgery (day 21). The amniotic membrane was transported in media to the Eye Theatre at Greenlane Hospital, Auckland District Health Board, for the planned intervention.

Histological examination of the cultured cells reveals mixed corneal and limbal phenotypes, with less than 10% of cells demonstrating cell surface markers consistent with limbal stem cells. Nonetheless, this may reflect the composition of the limbal cell population in vivo, although no studies have yet classified and quantified the types and proportions of cells that persist in the host eye.

Limbal stem cell transplant

In order to create a surface on which the stem cells are able to establish, fibrovascular and scar tissue were removed from the host ocular surface by superficial ketatectomy, until healthy superficial corneal stroma and bare adjacent sclera were exposed. If scar tissue was present more deeply within the host corneal stroma, particularly over the visual axis, then it may have been necessary to subsequently perform a corneal transplant in addition to the limbal stem cell transplant.

The limbal stem cells cultured on substrate were then placed on the prepared ocular surface. When the substrate is amniotic membrane it may be positioned corneal epithelium ‘down’ (i.e. cells on the host surface and covered by the amniotic membrane) or epithelium ‘up’ (i.e. with the amniotic membrane interposed between the cells and the host surface). The theoretical advantage of the latter technique is that the cells are grafted with the basement membrane of the amnion in situ, which eventually becomes absorbed into the host cornea. Success has been reported with either method and both techniques have their advocates. The authors have used both techniques but have achieved more consistent success with the epithelium down regime[15]. All four cases presented here involved the epithelium down technique. In this series the amniotic membrane was secured to the ocular surface with fine gauge sutures (either 10/0 Vicryl or Nylon), and protected with a bandage contact lens.

Post-operative care typically included preservative-free lubricants, topical antibiotics and topical corticosteroids. In addition, for allografts, consideration must be given to systemic immunosuppression including oral corticosteroids and second line agents such as mycophenolate mofetil or tacrolimus. This systemic approach was not necessary in the three autograft cases but was used in case 2, which required an allograft due to bilateral disease.

Case Summaries

Case 1

A 42-year male with severe chemical injury to left eye due to caustic soda, presented with perception of light vision and, following copious irrigations was treated with our “standardized”, intensive topical and systemic medical treatment. However, he developed a grey, scarred cornea and non-healing epithelial defect. He required three AMT within the first 3 months to enable healing. He subsequently underwent a superficial keratectomy and LSC autograft at 16 months with further keratectomy and two more LSC autograft over the next month. At 26 months he underwent a penetrating keratoplasty (PKP) and 4th LSC autograft. Four years post-injury, cataract surgery was performed. A year later vision was maintained at 20/40 best corrected vision (New Zealand driving standard), and the cornea was clear.

Case 2

A 36-year female with bilateral severe chemical burns to both eyes due to self-administration of extract of leaves from the plant Cestrum nocturnum. These drops were applied as a form of “natural” healing for ocular involvement by systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). The patient required emergency bilateral penetrating keratoplasty and a repeat tectonic right PKP was later required to preserve the eye. Six years after the original injury, the right cornea perforated due to a corneal melt. This was stabilised with glue and definitive surgery was scheduled. A PKP with LSC allograft (from the patient’s sister) was performed 2 months later. Ten months post-surgery the cornea is clear and unaided vision was 20/100, improving to 20/50 with correction.

Case 3

A 21-year male sustained thermal and chemical injury to the left eye caused by a firework. The eye was irrigated thoroughly, and treated conservatively, but required an amniotic membrane graft for a non-healing epithelial defect. Nine months after the injury a LSC autograft was performed, using tissue harvested from the fellow eye. Once the corneal surface was stable, a full-thickness corneal graft was performed to address significant corneal scarring from the original injury. Three years after the LSC graft, the visual acuity was maintained at 20/30, the ocular surface was healthy and the cornea remained clear.

Case 4

A 35-year female suffered a severe penetrating eye injury at the age of 11. She had previously undergone two corneal transplants and strabismus surgery. At presentation to the authors’ department the right eye was effectively blind, with an oedematous, painful, cornea with early signs of limbal stem cell deficiency. Initially, corneal debridement with amniotic membrane transplant was performed for pain and to stabilize the corneal surface, followed two years later by a corneal transplant to achieve maximum comfort and rehabilitate the eye. Five years after the initial presentation, due to LSCD and increasing corneal pain a fourth corneal transplant was performed in conjunction with a LSC autograft in a final attempt to achieve ocular comfort and maintain ocular integrity. Two months post-surgery, the corneal graft was entirely clear, pain was fully resolved and vision had dramatically improved to 20/80. Unfortunately, six months post-transplant the patient emigrated and was lost to follow-up.

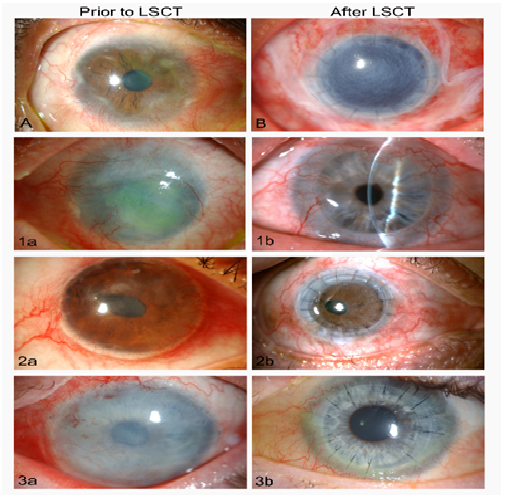

Illustrative images of cases with limbal stem cell deficiency and following limbal stem cell transplantation are highlighted in (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Images of eyes of patients with limbal stem cell deficiency (LSCD) and limbal stem cell transplants (LSCT).

A. An illustrative case of severe LSCD with vascularisation and irregular scarring of the limbus, spreading from the limbus towards the central cornea.

B. An unrelated eye with LSCD shown five days after treatment by superficial keratectomy, penetrating corneal transplantation (PKP) and a sutured, amniotic membrane transplant (AMT) supporting an ex-vivo expansion of limbal stem cells (AMT covering the cornea and adjacent conjunctiva).

1a. Case 1, extensive left corneal opacification and complete loss of limbal stem cells due to severe chemical injury. 1b. The same eye shown in 1b four years after LCST and PKP. Good vision (20/40) had been restored and maintained with a clear central cornea.

2a. Case 2, following a severe chemical injury shows a decompensating right corneal transplant with neovascularisation, an irregular epithelial surface and LSCD. 2b. the same eye shown in 2a. four months after superficial keratectomy, repeat PKP, and LCST showing a greatly improved ocular surface and clear corneal transplant with best vision of 20/50.

3a. Case 3, highlights an LCST with an amniotic membrane transplant sutured tightly over the cornea and limbus, following superficial keratectomy after a firework injury-related partial LSCD. 3b. The same eye 1 year after LSCT and PKP exhibits a healthy ocular surface and clear corneal transplant (at three years vision remained excellent at 20/30).

Discussion

Although our knowledge of stem cell activity in the cornea has grown exponentially in the last 25 years, there is still debate and discussion about the exact location of these stem cells. Notably, both limbal and central corneal cells can produce spheres in culture that have stem cell properties[16]. Our group have also demonstrated that following corneal injury, the proliferation and migration of corneal epithelium appears to be equally active in the limbus and in the central cornea[17]. Until the advent of limbal stem cell transplant, LSCD often resulted in total opacification of the cornea, with poor cosmetic and functional outcomes. Recent developments in surgical techniques and advances in cell biology have enabled increasingly sophisticated approaches to re-establishing a healthy ocular surface.

However, although three of the four eyes presented in the current study achieved a healthy ocular surface with visual acuity approximating driving license standards (20/30-20/60) and one subject with a good outcome was lost to follow-up, of twelve procedures followed-up between 6 month and 6 years the authors have identified a medium term success of 75%. Despite the relatively gradual process of repair and recovery, the success of this treatment has also been reported by others to be in the region of 70%, with success rates increasing with subsequent grafting procedures[18].

Ultimately, although the number of patients affected by LSCD is relatively small, the impact of this disease on visionand quality of life is so severe that it has generated enormous laboratory and clinical interest in the potential role of cultured LSCT[15,18]. None the less, patient selection is critical and stringentsurgical standards essential. All patients must be made aware of the risks and benefits of intervention including, length of recovery, prolonged medication, graft failure, potential for infection and the local and systemic effects of corticosteroids and immunosuppression.

Direction of future treatments

It has become clear that due to our increasing understanding of ocular and limbal stem cell biology our treatment options for unresponsive conditions are becoming more varied and sophisticated. However, it is also true that new treatments are limited only by what we do not yet understand. Indeed, the use of particular surgical techniques today may depend largely on clinical trial and error. However, the future refinement of limbal stem cell expansion and limbal stem cell therapies will be driven by laboratory research to better understand the molecular and cellular processes that underpin the success or failure of stem cell transplantation. The development of further refinements in LSCT techniques may be considered in four key domains: cell source, culture and expansion of cells, methods of implantation, and optimisation of the ocular environment.

Harvesting of cells

It has been established that autografting of limbal cells achieves far superior results than allografts, both in terms of graft survival and visual function[19]. Therefore it is preferable to harvest tissue from the patient whenever possible. The ability to harvest and expand a small volume of tissue from a healthy eye, or even from a healthy area of the injured eye, allows many more patients to receive autograft treatment. Only those with bilateral severe LSCD require tissue from an allograft source, with associated higher risks of graft failure, despite the use of topical and systemic immunosuppression[19].

Fortunately, advances towards future treatments indicate that epithelial cells may be harvested from non-ocular sites such as oral mucosa[20], or alternatively transdifferentiated from fibroblasts and cells from hair and skin into corneal epithelial phenotype, and implantation into animal and human subjects[21-23]. These methods include the generation of induced pluripotent stem cells from a patient’s skin or hair follicle to be used as autografts for LSCD.

Culture and expansion of cells

The optimal substrate for culture of LSC’s has yet to be identified. Although amniotic membrane has the convenience of a material that can be sutured onto the ocular surface, it is not necessarily the ideal environment for LSC culture. Alternative media and feeder/support cells have been investigated including dermal fibroblasts, Tenon’s capsule fibroblasts and limbal mesenchymal cells[24,25]. Established expansion techniques have also relied on media supplemented with animal-derived products and cells, with attendant risks of disease transmission. Recently, reports have been published of the non-animal based culture of limbal stem cells[26] and oral mucosal epithelial cells[27] that have been successfully implanted, with reversal of corneal disease.

Alternatives and methods of implantation

In addition to implantation via AMT and contact lenses, other vehicles for LSC transplantation have been explored. These include cultured mucosal sheets[28], synthetics[29], and an artificial limbus[30]. Alternative reported subtrates include: collagen, fibrin, silk fibroin, human anterior lens capsule, keratin, poly (lactide-co-glycolide), polymethacrylate, and hydroxyethylmethacrylate[31]. A simplified version of the technique has been proposed, in which harvest of the biopsy and implantation are performed in a single step[32].

Sphere forming cells as future limbal implants

The refinements in limbal stem cell treatments being investigated all revolve around obtaining the optimal cell composition of the grafted material, providing the optimal carrier substrate for the cells and in supporting their successful integration into the compromised cornea. The ultimate goal would be a stem cell implant that is capable of reforming the stem cell niche within the limbus that is capable of long term self-regeneration and response to secondary injuries.

To this aim our laboratories have been working on isolating sphere forming cells from human cadaver limbal tissue that are capable of long term survival in culture but on exposure to collagen matrices are capable of colonization and stabilization of that matrix[33]. The cells within these spheres are likely a combination of limbal epithelial stem cells and limbal mesenchymal stem cells and can give rise to epithelial or mesenchymal cell types.

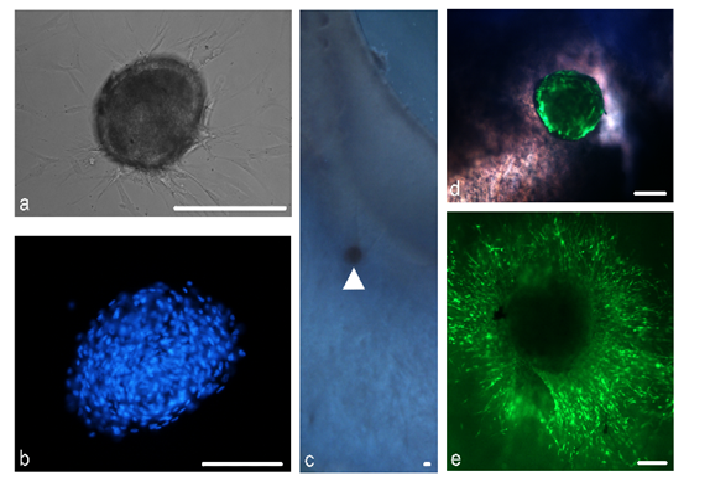

These spheres form distinct, tightly packed structures composed of cells, which are bounded by a smooth surface (figure 4a and b). Spheres stain positively for the stem cell markers δNp63α, ABCG2 as well as the recently purported limbal stem cell marker ABCB5[34]. Spheres were found to stain positivelyfor markers of various niche characteristics including notch-1, a basal limbal epithelial marker, laminin, a marker of the corneal epithelial basement membrane and keratocan, a corneal stroma proteoglycan.

Furthermore, we have investigated the use of peripheral corneal spheres in ocular surface repopulation. Spheres implanted into donor corneo-scleral rims (figure 4c and d), remain in situ and show signs of cell proliferation and migration (figure 4e) to repopulate the donor tissue. Our continuing studies focus on the potential use of spheres to improve the stem cell characteristics of amniotic membrane based grafts or even replace them completely for improved treatment of patients with limbal stem cell deficiency.

Figure 4: Spheres and tissue repopulation. A phase contrast microscope image of a sphere with distinct borders is shown (a) DAPI staining of cell nuclei show tightly packed cells within the sphere (b) Spheres can be implanted near the limbal region in a corneo-scleral rim (c) (arrowhead) An overlaid phase contrast and green fluorescence image shows the fluorescently labelled sphere within tissue (d) Over time, the sphere provides cells which migrate to repopulate the immediate surrounding tissue (e) Scale bar = 100 μm

Conclusion

LSCT has increasingly become an established treatment for LCS failure, to the point where it has been referred to by some as an intervention that has “come of age”[35]. Although we now have increasingly reliable methods for rehabilitating the ocular surface, as well as tools for evaluating their success, this technique remains outside the scope of mainstream ophthalmic care and continues to be refined. In the same way that the implantation of intra-ocular lenses progressed from experimental to universal over several decades[36], we can justifiably hope that optimization of tissues and surgical techniques, will, in due course, enable the restoration of vision to the many blind from intractable corneal disease with limbal stem cell deficiency.

Acknowledgment

Professor Charles McGhee MBChB PhD FRCOphth, an experienced, sub-specialist, corneal transplant surgeon holds full responsibility for the informed consent, surgical procedures, and post-operative management of the clinical cases presented and is the guarantor of the accuracy of clinical outcome data.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations: ABC: Antigen binding cassette; AMT: Amniotic membrane transplant; DAPI: Diamidinophenylindole; LSC: Limbal stem cells; LSCD: Limbal stem cell deficiency; LSCT: Limbal stem cell transplant; PKP: Penetrating keratoplasty.

References

- 1. Whitcher, J.P., Srinivasan, M., Upadhyay, M.P. Corneal blindness: A global perspective. (2001) Bull WHO 79(3): 214-221.

- 2. Ahmad, S. Concise review: Limbal stem cell deficiency, dysfunction, and distress. (2012) Stem Cells Transl Med 1(2): 110-115.

- 3. Tsubota. K., Satake, Y., Ohyama, M., et al. Surgical reconstruction of the ocular surface in advanced ocular cicatricial pemphigoid and Stevens-Johnson syndrome. (1996) Am J Ophthalmol 122(1): 38-52.

- 4. Nelson, L. B., Spaeth, G. L., Nowinski, T.S., et al. Aniridia review. (1984) Surv Ophthalmol 28(6): 621-642.

- 5. Tseng, S.C. Regulation and clinical implications of corneal epithelial stem cells. (1996) Mol Biol Rep 23(1): 47-58.

- 6. Thoft, R. A., Friend, J. The X, Y, Z hypothesis of corneal epithelial maintenance. (1983) Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 24(10): 1442-1443.

- 7. Tseng, S.C., Hirst, L.W., Farazdaghi, M., et al. Inhibition of conjunctival transdifferentiation by topical retinoids. (1987) Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 28(3): 538-542.

- 8. Kenyon, K. R., Tseng, S.C. Limbal autograft transplantation for ocular surface disorders. (1989) Ophthalmology 96(5): 709-723.

- 9. Jenkins, C., Tuft, S., Liu, C., et al. Limbal transplantation in the management of chronic contact-lens-associated epitheliopathy. (1993) Eye 7(5): 629-633.

- 10. Pellegrini, G., Traverso, C. E., Franzi, A.T., et al. Long-term restoration of damaged corneal surfaces with autologous cultivated corneal epithelium. (1997) Lancet 349(9057): 990-993.

- 11. Rama, P., Bonini, S., Lambiase, A., et al. Autologous fibrin-cultured limbal stem cells permanently restore the corneal surface of patients with total limbal stem cell deficiency. (2001) Transplantation 72(9): 1478-1485.

- 12. Di, Girolamo, N., Bosch, M., Zamora, K., et al. A contact lens-based technique for expansion and transplantation of autologous epithelial progenitors for ocular surface reconstruction. (2009) Transplantation 87(10): 1571-1578.

- 13. Tsai, R.J., Li, L., Chen, J. Reconstruction of damaged corneas by transplantation of autologous limbal epithelial cells. (2000) New Engl J Med 343(2): 86-93.

- 14. LenÁová, A., Pokorná, K., Zajícová, A., et al. Graft survival and cytokine production profile after limbal transplantation in the experimental mouse model. (2011) Transplant Immunol 24(3): 189-194.

- 15. Harkin, D.G., Apel, A.J, Di, Girolamo, N., et al. Current status and future prospects for cultured limbal tissue transplants in Australia and New Zealand. (2013) Clin Exp Ophthalmol 41(3): 272-281.

- 16. Chang, C.A., McGhee, J.J., Green, C.R., et al. Comparison of stem cell properties in cell populations isolated from human central and limbal corneal epithelium. (2011) Cornea 30(10): 1155-1162.

- 17. Chang, C., Green, C.R., McGhee, C.N.J., et al. Acute wound healing in the human central corneal epithelium appears to be independent of limbal stem cell influence. (2008) Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 49(12): 5279-5286.

- 18. Shortt, A.J., Secker, G.A., Notara, M.D., et al. Transplantation of ex vivo cultured limbal epithelial stem cells: a review of techniques and clinical results. (2007) Survey of ophthalmology Oct 31 52(5): 483-502.

- 19. Özdemir, Ö., Tekeli, O., Örnek, K., et al. Limbal autograft and allograft transplantations in patients with corneal burns. (2004) Eye 18(3): 241-248.

- 20. Nishida, K., Yamato, M., Hayashida, Y., et al. Corneal reconstruction with tissue-engineered cell sheets composed of autologous oral mucosal epithelium. (2004) New Engl J Med 351(12): 1187-1196.

- 21. Meyer-Blazejewska, E.A., Call, M.K., Yamanaka, O., et al. From hair to cornea: Toward the therapeutic use of hair follicle-derived stem cells in the treatment of limbal stem cell deficiency. (2011) Stem Cells 29(1): 57-66.

- 22. Scafetta, G., Tricoli, E., Siciliano, C., et al. Suitability of human Tenon’s fibroblasts as feeder cells for culturing human limbal epithelial stem cells. (2013) Stem Cell Rev Rep 9(6): 847-857.

- 23. Hayashi, R., Ishikawa, Y., Ito, M., et al. Generation of Corneal Epithelial Cells from Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells Derived from Human Dermal Fibroblast and Corneal Limbal Epithelium. (2012) PLoS ONE 7(9).

- 24. Subramaniam, S., Sejpal, K., Fatima, A., et al. Coculture of autologous limbal and conjunctival epithelial cells to treat severe ocular surface disorders: Long-term survival analysis. (2013) Indian J Ophthalmol 61(5): 202-207.

- 25. Nakatsu, M.N., González, S., Mei, H., et al. Human limbal mesenchymal cells support the growth of human corneal epithelial stem/progenitor cells. (2014) Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 55(10): 6953-6959.

- 26. Zakaria, N., Possemiers, T., Dhubhghaill, S.N., Leysen, I., et al. Results of a phase I/II clinical trial: Standardized, non-xenogenic, cultivated limbal stem cell transplantation. (2014) J Transl Med 12(1): 58.

- 27. Kolli, S., Ahmad, S., Mudhar, H.S., et al. Successful application of ex vivo expanded human autologous oral mucosal epithelium for the treatment of total bilateral limbal stem cell deficiency. (2014) Stem Cells 32(8): 2135-2146.

- 28. Hata, K., Kagami, H., Ueda, M., et al. The characteristics of cultured mucosal cell sheet as a material for grafting; Comparison with cultured epidermal cell sheet. (1995) Ann Plast Surg 34(5): 530-538.

- 29. Deshpande, P., Ramachandran, C., Sefat, F., et al. Simplifying corneal surface regeneration using a biodegradable synthetic membrane and limbal tissue explants. (2013) Biomaterials 34(21): 5088-5106.

- 30. Ortega, Í., Deshpande, P., Gill, A.A., et al . Development of a microfabricated artificial limbus with micropockets for cell delivery to the cornea. (2013) Biofabrication 5(2): 025008.

- 31. Feng, Y., Borrelli, M., Reichl, S., et al. Review of alternative carrier materials for ocular surface reconstruction. (2014) Curr Eye Res 39(6): 541-552.

- 32. Sangwan, V.S., Basu, S., MacNeil, S., et al. Simple limbal epithelial transplantation (SLET): A novel surgical technique for the treatment of unilateral limbal stem cell deficiency. (2012) Br J Ophthalmol 96(7): 931-934.

- 33. Yoon, J.J., Wang, E.F., Ismail, S., et al . Sphere-forming cells from peripheral cornea demonstrate polarity and directed cell migration. (2013) Cell Biol Int 37(9): 949-960.

- 34. Ksander, B.R., Kolovou, P.E., Wilson, B.J., et al. ABCB5 is a limbal stem cell gene required for corneal development and repair. (2014) Nature 511(7509): 353-357.

- 35. Ramachandran, C., Basu, S., Sangwan, V.S., et al. Concise review: The coming of age of stem cell treatment for corneal surface damage. (2014) Stem Cells Transl Med 3(10): 1160-1168.

- 36. Apple, D.J., Ram, J., Foster, A., et al. Elimination of cataract blindness: a global perspective entering the new millenium. (2000) Surv Ophthalmol 45 Suppl 1: S1-196.